This is the text of a paper I delivered at the Literary London Conference a few years ago, and which forms the basis of part of one of the chapters in my PhD thesis. The majority of it has been substantially reworked, but I still stand by the arguments, so I’m posting it here with the rest of my Situationist work.

The term psychogeography has achieved a level of ubiquity in the discussion of a number of contemporary London writers, most prominently Iain Sinclair, and indeed, Sinclair’s use of the word within his work at least in part explains its current popularity. The word has a certain anti-establishment cachet, having its origins within the slightly disreputable milieu of the Parisian post-war revolutionary avant-garde, where it was formulated by members of the Lettriste International, and was subsequently taken up by its better known (if not notorious) successor, the Situationist International. The concept is undeniably deeply resonant, suggestive at the very least of a pseudo-scientifc or poetic understanding of the relationship between geography and psychology and the imaginative possibilities to be found in the urban environment. In the following oft-quoted definition given by the leader of the Situationists, Guy Debord, psychogeography is ‘the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals’.[1] The principal method for the study of these phenomena was the dérive or drift in which ‘one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.’[2] Contemporary London psychogeography has much in common with its Parisian forebear: the concepts that Debord outlines can, for example, be mapped comfortably onto Iain Sinclair’s programmatic methodological statement in his book Lights Out for the Territory, in which he states that

Walking is the best way to explore and exploit the city; the changes, shifts, breaks in the cloud helmet, movement of light on water. Drifting purposefully is the recommended mode, tramping asphalted earth in alert reverie, allowing the fiction of an underlying pattern to reveal itself.[3]

The technique of drifting, navigating the city on foot, the reading of the city in terms of the psychological effect that it has upon the individual that are present in the Situationist definition of psychogeography are all present in Sinclair’s understanding of it. However, if one examines the development of the concept from its emergence in 1950s Paris to its contemporary London usage, whilst the methodological foundations of psychogeography remain more or less constant, its teleological assumptions have shifted radically.

Where in its original formulation, psychogeography was to be understood as a field of knowledge that would inform the creation of a post-revolutionary ‘Situationist city’, contemporary psychogeography as it is practised by Sinclair harbours no such world-transforming ambitions, and indeed could be read as being openly hostile to such projects. Instead, contemporary London psychogeography finds its expression as a literary mode, a position that would have appeared paradoxical to its original practitioners: Debord even goes so far as to assert that the dérive is inimical to such representation, claiming that ‘written descriptions can be no more than passwords to this great game’.[4] This opens the question as to how and why this shift in emphasis from revolutionary spatial practice to textual representation has occurred, and what implications there might be as a result. Moreover, whilst Sinclair is quite open about the fact that his usage of the term is different to that of the Situationists, it is telling that in an interview with Kevin Jackson he states that he ‘wanted it include everything’.[5] Arguably, there is a danger that if one approaches psychogeography uncritically and without an awareness of its development, the concept becomes abstract and the crucial differences of approach between its historical and contemporary usages are effaced.

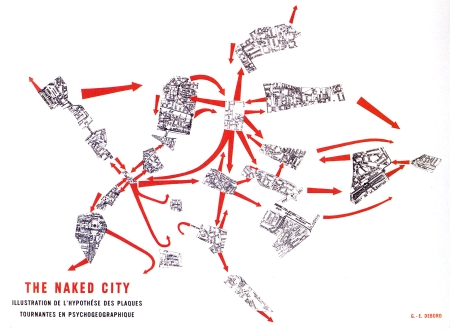

The scope of this change and its significance can be dramatically illustrated through the comparison of two psychogeographic maps: Guy Debord’s 1957 work The Naked City, and Dave McKean’s map of London ‘The 8 Great Churches: The Lines of Influence the Invisible Rods of Force Active in this City’ found in the 1998 edition of Sinclair’s 1975 poem Lud Heat. These two works both offer interpretations of their respective cities that re-imagine their physical and imaginative spaces and in the process profoundly subvert conventional understandings of cartography, and in this they reveal the similarities that exist between the Parisian and London variants of psychogeography: both attempt to critique hegemonic representations, readings and reconfigurations of urban space. As Sinclair stated in the plenary address to this conference, ‘when the story is imposed, it all starts to fall apart.’ Psychogeography, in its historical and contemporary versions, attempts to find alternative narratives to the ‘official’ ones, to allow the city to speak in its own voice, and these two maps both illustrate potential alternative readings of city space. However, when one examines the ways in which each map presents its alternative narrative, the vastly differing scope of their ambitions is revealed.

Before I go on to examine the maps in detail, it is useful to give some context: for the Situationists, the city was the prime site of their activity, both as object of criticism and as inspiration. Debord stated that ‘from any standpoint other than that of police control, Haussmann’s Paris is a city built by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’[6] He identifies in the rationality of its design a concern only for utility and the circulation of traffic, failings that were only increased in the technocratic visions of the high Modernism of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus. Not only were these factors in the alienation and isolation of the city’s inhabitants, they were, most seriously, monotonous. For the Situationists, therefore, the modern city was a problem to which a solution must be found. In a text entitled ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’ that was both lament and eulogy for the possibility that the city represented for the Situationists, Ivan Chtcheglov stated

We are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun. Between the legs of the women walking by, the dadaists imagined an monkey wrench and the surrealists a crystal cup. That’s lost. We know how to read every promise in faces—the latest stage of morphology. The poetry of the billboards lasted twenty years. We are bored in the city, we really have to strain to still discover mysteries on the sidewalk billboards, the latest state of humor [sic] and poetry.[7]

With his famous plea that ‘the hacienda must be built’,[8] he goes on to describe in rhapsodic terms a city that ‘could be envisaged in the form of an arbitrary assemblage of castles, grottoes [sic] , lakes, etc.’, the districts of which ‘could correspond to the whole spectrum of diverse feelings that one encounters by chance in everyday life.’[9] In such a city, in Chtcheglov’s words, ‘everyone will live in their own personal “cathedral,” so to speak. There will be rooms more conducive to dreams than any drug, and houses where one cannot help but love.’[10] Psychogeography was envisioned as the means to rediscover the ‘mysteries on the sidewalk billboards’, to re-enchant the city in opposition to the schematic and sterile visions of the city planners.

As I have mentioned, the primary method by which the Situationists investigated psychogeographical phenomena was through the dérive, in which the participants would wander through the city on foot according to whim, and to a lesser degree, chance. In his essay ‘Theory of the dérive’, Guy Debord asserts that by engaging in such a practice, the dériver or more frequently, dériveurs, would be able to discern the ‘psychogeographical relief’ of the city, the ‘constant currents, fixed points and vortexes which strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.’[11] Debord states that because of the ‘playful-constructive’ nature of the activity, the dérive is ‘completely distinguish[ed] … from the classical notions of the journey or the stroll.’[12] The British artist Ralph Rumney, a former member of the Situationist International, helpfully elucidates:

dérive – it’s a French word that’s become pretentious now, there’s been a sort of sacralisation of it – it basically means wandering, but as Debord defined dérive it was going from one bar to another, in a haphazard manner, because the essential thing was to set out with very little purpose and to see where your feet led you, or your inclinations … You go where whim leads you, and you discover parts of cities, or come to appreciate them, feel they’re better than others, whether it’s because you’re better received in the bar or because you just suddenly feel better.[13]

It was with ‘data’ gathered from practices such as these that Debord created The Naked City, which goes some way towards illustrating the Situationist understanding of psychogeography. The work consists of a map of Paris that has been cut up and reassembled, not in accordance with the representation of the physical terrain, but according to ‘unities of ambiance’.[14] Red arrows connect the different quartiers according to the feelings they inspire, the continuity of ‘sense of place’ between geographically separated areas, providing a representation of the ‘fixed points and vortexes’, the ebb and flow of the atmosphere of place that Debord evokes in ‘Theory of the dérive’. In so doing, The Naked City presents with us a radically subjective reading of the city, and in the process subverts the claims to objectivity made by conventional maps. The ‘gods-eye-view’ with which the ordinary map of Paris presents its user is an abstraction that excels at schematising geography, yet effaces the experience of the city as it is perceived at ground level. Or, to put it another way, it is very good at telling its users where they are going, but is near-useless at telling them what it will be like when they get there. Debord’s map inverts this hierarchy and reasserts the primacy of the city as it is experienced rather than as it is abstracted, its poetic possibility over its utility. The most nebulous and subjective quality of the environment, its atmosphere as Debord perceives it, is taken as subject for representation. The non-existent, and, indeed impossible viewpoint of the conventional map is therefore questioned and, as Tom McDonough contends, a map which operates ‘as narrative rather than as tool of “universal knowledge”’[15] is presented instead.

When one compares The Naked City to Dave McKean’s map in Lud Heat, a number of parallels can be drawn between this and Debord’s work. As with The Naked City, the map that accompanies Sinclair’s poem presents a vision of the city that it takes as subject that subverts conventional mappings of it. A subjective reading of the city is again asserted in contestation to the claims towards objectivity that more schematic renderings of London might make, asserting the truth of the city as it is subjectively experienced over its abstractions. When a conventional map attempts to represent the physical layout of the city in order to orient its users, not least of the features included are the city’s streets: in McKean’s map these have been replaced by a series of speculative alignments linking sites of ‘occult power’,[16] primarily the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor but also landmarks including the Greenwich Observatory and the British Museum, between which flows an undefined ‘force’. Indeed, all other features have been reduced to insignificance, and the whole concept of the map as an object to be utilised for navigation is subverted by a rendering which depicts London as a darkly gothic city haunted by a malignant past.

This is emphasised further when one analyses Sinclair’s text. Hawksmoor’s churches have an ‘unacknowledged magnetism and control-power’, Sinclair speculates, that has led to a historic legacy of violence that has inscribed itself on the landscape of London and reaches into the present. He specifies:

the ritual slaying Marie Jeanette Kelly in the ground floor room of Miller’s court, Dorset Street, directly opposite Christ Church … the Ratcliffe Highway slaughter of 1811, with the supposed murderer, stake through heart, trampled into the pit where four roads cross to the north of St George-in-the-East … the battering to death of Mr Abraham Cohen, summer of 1974, on Cannon Street Road (one spoke of the quadrivium): £110,000 in old banknotes in the kiosk behind him, stuffed in cocoa tins and cigarette packets; three ritualistic coins laid at his feet, as the were in 1888 at the feet of Mary Ann Nicholls, the first Ripper victim.[17]

Each murder is ascribed its place on the territory, the landscape and its history become indivisible. Moreover, in connecting the older crimes with one contemporary with the poem’s composition, Sinclair emphasises the hold that the past has over the present, and it is precisely this claim that asserts itself in the map. It is the dark memories, the occult weight of history, that McKean’s rendering of the city depicts. The primacy of Hawksmoor’s Churches in McKean’s map is in itself an assertion of the past’s claim upon the present – with all other landmarks removed the perspective of an historic (and ‘subservient’) ‘grounded eye’,[18] is simulated, recreating a London whose horizons are ‘differently punctured’[19] by church spires. Much as with the Situationist critique of Paris, this vision is at odds with that of the processes of redevelopment that were beginning to operate at the time Lud Heat was being composed: Sinclair states of the period in which Lud Heat was written that ‘it was as if the landscape was breaking up like an ice floe, and there were voices still registering, there were manifestations that weren’t subsequently available … because it all too soon disappeared under serious development.’[20] McKean’s map suggests that these voices are not easily hushed, and that the ‘horribly unappeased’[21] crimes of the past will not be easily overwritten by contemporary re-developments.

Both maps, The Naked City and ‘The 8 Great Churches’, subvert conventional cartography and assert subjective readings over objective abstractions of city space. However, the composition of The Naked City reveals the essential difference between the psychogeography of the Situationists and Sinclair’s practice: where Parisian psychogeography orients its critique of the city around a utopian projection towards a newly revivified post-revolutionary city, London psychogeography finds the strength of its critique in the past. The Naked City is constructed from fragments of a conventional map, and it is this that reveals the scope of the Situationists’ ambitions: whilst the work undermines the rationalising, hegemonic viewpoint of the city planner, the fact that it shatters the existing fabric of Paris and remodels it according to subjectively perceived ‘unities of ambience’ demonstrates the Situationists’ desire to fundamentally transform the nature of the city. This is only enhanced when one compares this work to the drawings and models made for a Situationist city, New Babylon, by the Dutch architect and member of the Situationist International, Constant Nieuwenhuys. This is what Situationist psychogeography strives towards, and in this it remains fundamentally optimistic about both the form of knowledge produced by the dérive and the liberatory promise of technology, revolutionary politics, and the transformative power of art.

Debord stated that ‘psychogeography’s progress depends to a great extent on the statistical extension of its methods of observation’.[22] Until this has occurred ‘the objective truth of even the first psychogeographic data cannot be ensured. But even if these data should turn out to be false, they would certainly be false solutions to a genuine problem.’[23] Debord seems to be suggesting that with more psychogeographic maps, more dérives, it would be possible to aggregate an objective, or in Hegelian terms, concrete universal truth about the nature of the city as it is experienced, and from this knowledge a city such as New Babylon could have been constructed. Yet how could a map such as The Naked City be anything other than a representation of a purely subjective experience? Or, to put it another way, how could one express the nature of the experience of dérive in a way which was not merely self-expression, that is, art?

This faith in the potential for finding truth through the practise of dérive is precisely what marks the difference between Parisian and London psychoegeography. The Lud Heat map, in leaving the geography of London intact, offers us an alternative vision of the city, yet at no point does Sinclair suggest that this vision is in any way objectively true. Whilst he claims a certain authority from the voices that he unearths, stating in a never-broadcast radio documentary on Lud Heat that ‘[p]lace activates the poet; the poet is drawn to a specific location, to activate a monologue that is already available there’,[24] the presence of Sinclair’s house on the Lud Heat map as one of the sites of power in the constellation of influences that he suggests criss-cross the city suggests, at the very least, that his dark intimations are not necessarily to be taken at face value. What Sinclair’s text and the accompanying map offer us is an interpretation, not a plan for the future, and, as Henri Lefebvre reminds us in The Production of Space,

When codes worked up from literary texts are applied to spaces – to urban spaces, say – we remain, as may easily be shown, on the purely descriptive level. Any attempt to use such codes as a means of deciphering social space must surely reduce that space itself to the status of a message and the inhabiting of it to the status of a reading.[25]

Sinclair’s accounts of his dérives are exactly this: descriptions which reduce space to a (necessarily subjective) reading. This is precisely what is being hinted at in Lights Out for the Territory when he refers to the ‘underlying patterns’ that he discerns in the environment as ‘fiction’.[26] In acknowledging that such textual descriptions are themselves both partial and reductive, and thus concurring with Debord’s assertion that they can be no more than ‘passwords’,[27] Sinclair’s materials become, not, as the Situationists hoped could eventually be the case, the city itself, but instead the narratives and myths that come through time to be associated with it – in short art and history. In transforming the materials of psychogeography in such a fashion and abandoning any hope of going beyond a subjective reading of the city, Sinclair maintains its power as critique, yet rejects its claims to truth, and, moreover, divests it of the utopian tendencies that operate in its original, Situationist, formulation.

[1] Debord, Guy, ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, in Knabb, Ken (ed.) Situationist International Anthology, (Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1980), p. 5.

[2] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 50.

[3] Iain Sinclair, Lights Out for the Territory, (London: Granta, 1997), p. 4.

[4] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, in Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 53.

[5] Kevin Jackson and Iain Sinclair, The Verbals, p. 75.

[6] Guy Debord, ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography’,

[7] Ivan Chtcheglov, ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 1. Although originally written in 1953, so before the establishment of the Situationist International in 1957, this article was reprinted in the Issue 1 of International Situationniste.

[8] Ivan Chtcheglov, ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 1.

[9] Ivan Chtcheglov, ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, pp. 3-4.

[10] Ivan Chtcheglov, ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 3.

[11] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 50.

[12] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 50.

[13] Alan Ward, The Map Is Not The Territory, p. 169.

[14] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, p. 53.

[15] Tom McDonough, ‘Situationist Space’, in Tom McDonough, Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, p. 243

[16] Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, (London: Granta, 1998), p. 15.

[17] Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, p. 21.

[18] Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, p. 13.

[19] Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge, p. 13.

[20] Kevin Jackson, The Verbals: Kevin Jackson in Conversation with Iain Sinclair (Tonbridge: Worple Press, 2003), p. 74.

[21] Kevin Jackon, The Verbals, p. 116.

[22] Guy Debord, ‘Report on the Construction of Situations and on the Terms of Organization and Action of the International Situationist Tendency’, in McDonough, Tom (ed.), Guy Debord and the Situationist International (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), p. 45.

[23] Guy Debord, ‘Report on the Construction of Situations’, p. 45.

[24] Peter Green, ‘The Lud Heat Documentary’, found at

[25] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), p. 7.

[26] Iain Sinclair, Lights Out for the Territory, p. 4.

[27] Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, in Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, p. 53.